I was in the US Army Reserves for eight years.

Like every other soldier who took the oath, I went to Basic Combat Training. For me, it was Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri. We called it Fort “Lost-in-the-Woods”, owing to the fact it was in the middle of nowhere.

Like every other soldier, I was issued a weapon–the standard-issue M-16A2 5.56 caliber assault rifle. It weighs 8.8 pounds (4kg) unloaded and I carried it everywhere with me. I slept with it. I schlepped it all over the damn forest and back again. I took it apart, cleaned it, and put it back together more times than I care to remember.

Eventually, I had to learn how to fire the thing.

Qualifying on the M-16 was a requirement for graduation. After only a week’s training using the weapon, the whole company trotted out to the range to engage in firing live rounds at plastic targets. Shaped like human silhouettes, these targets were set at various distances ranging from 25 meters up to 300 meters. They would pop up and stay up for different time intervals before dropping.. The closer they were, the quicker they’d pop up and drop.

We were given two magazines filled with twenty “rounds” (bullets) each–one to be fired in the “prone supported” (lying down with the rifle on sandbags) and one to be fired in the “prone unsupported” (lying down and firing from your elbows) position. A passing score was 23 out of 40. That made you a “marksman”. 30 to 35 earned you the title of “sharpshooter”. 36 and above was the coveted “expert” title.

Man, I wanted that expert badge.

My brother, a Marine, had placed at the top of his company’s marksmanship scores in boot camp. I wanted to prove I was as good. I wanted to show him that badge and say: “Look, I can do this too.”

Sliding Downhill from Pre-Qualification

On my first pre-qualification attempt I scored a 33–an 82.5% score, or a B minus. “Not bad,” I figured. Three more targets wasn’t that big of a barrier to overcome. “If I shoot only a little better tomorrow, I’m in the money.”

On my second and last pre-qualification attempt for the day, my score dipped to 31. I began to panic. Not only was I not getting closer, but I was dangerously close to not making sharpshooter (30-35). I exited the firing range feeling anxious about the next day’s prospects.

Fear and Qualifying in Fort Lost-in-the-Woods

It was “Qual Day”. We loaded ourselves into the cattle cars (yes, literal cattle cars) and trucked out to the range. I drank and ate little, nervous as I was. When it was my turn, I filed out to the firing line, took up my firing position, and engaged the targets.

I ended that day at a 31. Out of 40, that’s a 77.5%, or a C+. I failed to achieve my goal, and I took it as a personal failure. I earned a sharpshooter badge and wore it on my uniform the rest of my days in the Army, never overcoming the score or the disappointment I felt in myself for not achieving my goal.

I left the Army in 2012, shortly before moving overseas to China. My uniform, and the sharpshooter metal on it, is still at home in the closet of my childhood bedroom.

Modern Marksmanship and Ancient Archery

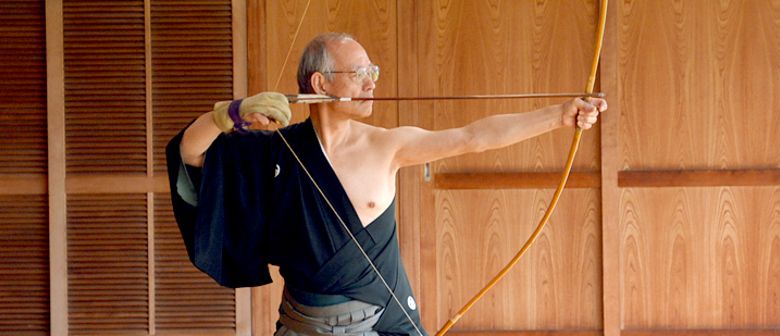

Kyūdō (弓道) is the Japanese “Way of Archery”. Much like Sadō, it is also considered a spiritual path to enlightenment in traditional Zen teachings.

The highest ideal of kyūdō is seisha seichū (正射正中), or “correct shooting, correct hitting”. In this ideal, practitioners of Japanese archery believe the arrow will always find its target when the archer’s mind, body, and spirit are aligned. This approach puts the emphasis on the shooter, not the shot.

At the pinnacle of mastery, archers perform the incredible feat of striking a target in darkness:

Hitting a target in complete darkness is taken as a given for the masters of the art of kyūdō–it’s expected the archer hits the target when all other things proceed appropriately. Unlike athletes celebrating a score or a victory over an opponent, the archer does not celebrate striking the target. Rather, it would be crude to show any emotion over the result of the shot. To do so demonstrates poor mastery over the self and a lack of understanding of the essence of kyūdō itself.

Perhaps it sounds silly to some, but it makes perfect sense to me. After all, there is nothing left to be done once the arrow is loosed from the bow. It will proceed according to its own nature and land where it wills. The archer has full control up until the moment of release, and can do nothing but let their spirit sail away on the arrow thereafter.

My Spirit in a Bowl of Tea

It’s hard to imagine a situation with lower stakes than whisking a bowl of matcha.

Unlike the the soldier, at no point will I ever be expected to save my life or someone else’s based on the quality of my tea. And yet, I’ve still found opportunity to worry.

There’s a moment of release in tea ceremony: the moment when the host finishes preparing the tea and passes it off to the guest for them to enjoy. Like an arrow released from a bow, the mind, body, and spirit of the host culminates in a singular bowl of tea.

I often find myself worrying whether I’ve done a good job. Will the guest like the flavor? Is the matcha fully incorporated? Is the froth whisked well to create a pleasing texture? Unable to taste the tea for myself, my mind is left to worry. It’s only natural to concern ourselves with the guest in tea ceremony–the whole occasion centers around the relationship between the host and guest–but it’s wasted effort. As long as I’ve acted appropriately to make the tea, the result can only be enjoyable.

Using seisha seichū in Everyday Life

Shooting is a process. Archery is a process. Tea is a process. Life is a process.

What if we ignored the outcome and instead just focused entirely on the systems that create processes?

Like a pilot flying from New York to L.A., the destination focuses the journey and allows us to orient ourselves accordingly. Thing is, the pilot still has to fly the plane. She can fully intend to end up in Los Angeles, but even a small change in the orientation of the plane at take-off spread over thousands of miles will put the plane in Mexico instead.

The journey never proceeds like we think it will. We imagine an easy path moving from A to B in a straight line. Reality often differs from expectation, and when the going gets tough, we fall–not rise–to the level of our processes and systems.

Here’s something else about goals: winners and losers both have the same goals. In any sports competition, both teams want to win. The loser focuses on the scoreboard. The winner focuses on moving the ball ahead one yard at a time. That’s process.

Look, goals are great. I don’t mean to say they aren’t helpful. But when we hold them up as the golden standard, we forget that no goal accomplishes itself. We must build systems to create process, and process is what gets us to where we’re going.

Cut Yourself Some Slack

If I could take a time machine back to 2006 to sit alongside 19 year-old me and coach myself on shooting, I’d tell him this. Unfortunately, much like the bullet from a gun and the arrow from a bow, time only flows in one direction. Instead, I get the chance to tell myself this today:

Masters of archery aren’t born, they’re made. With every draw of the bow, they give themselves another chance to improve. And so it is with life. With every new day, we get a new chance to try again.

So cut yourself some slack. Maybe you should have gotten the salad instead of the burrito for lunch. Get back to your diet at dinner. Maybe you shouldn’t have had that cigarette because you’re trying to quit. Don’t light the next one. If you miss the target, shoot again.

“Correct shooting, correct hitting.” As long as the archer acts appropriately, the arrow certainly strikes its target.

1 comment

Hello Mike,

Great stuff. I both like the metaphor and find it a very helpful picture for life.

Thanks.