Welcome back to The Tea Letter!

Today’s post continues to explore and expand on the theme of mushin (無心, “No-Mind-No-Thought”) that lies at the core of Zen philosophy, primarily according to Takuan Sōhō’s series of essays titled “The Unfettered Mind”.

If you haven’t yet, get caught up with the previous post I wrote on the subject here.

I want to keep digging in to some of the other wisdom contained in the first essay— “The Mysterious Record of Immovable Wisdom”—as it pertains to learning and mastery.

Let’s get to it.

The Beginner’s Territory

Something that jumped out at me about Takuan’s writings is his reference to the mind of the beginner as something close to the mind of the master. See here what he says about the beginner in martial arts:

…when one practices discipline and moves from the beginner’s territory to immovable wisdom, he makes a return and falls back to the level of the beginning, the abiding place.

This passage stuck with me. It’s the first time I’ve thought of the beginning and end of any “Way” being located in the same place.

He continues:

There is a reason for this.

Again we speak with reference to your own martial art. As the beginner knows nothing about either his body posture or the positioning of his sword, neither does his mind stop anywhere within him. If a man strikes at him with the sword, he simply meets the attack without anything in mind.

Here lies the core of the Beginner’s Territory. When residing in the Beginner’s Territory, one doesn’t think of what’s right or wrong, one simply does. If you’re being attacked, you just defend yourself. When moving, you just move.

In this way, the beginner is most like the master.

Departing the Beginner’s Territory—The Path to Mastery

Everything changes when we decide to walk the path of mastery and become a learner:

As [the beginner] studies various things and is taught the diverse ways of how to take a stance, the manner of grasping his sword and where to put his mind, his mind stops in many places. Now if he wants to strike at an opponent, he is extraordinarily discomforted.

If you read the last edition, the notion of the mind “stopping” will already be familiar to you. It’s an affliction born of a mix of knowledge and ignorance. At this point, we know enough to know whether we’re engaging in “proper” action.

The stoppage that occurs as one grows in knowledge and experience is inevitable, but it’s not permanent.

Later, as days pass and time piles up, in accordance with his practice, neither the postures of his body nor the ways of grasping the sword are weighed in his mind. His mind simply becomes as it was in the beginning when he knew nothing and had yet to be taught anything at all.

Time and training are the answer to the question of how we avoid stopping the mind and gain mastery. It’s also the key to understanding how the beginner and the master are most alike.

The Beginner and the Master are Adjacent

What exactly does it mean for the beginner and the master to be “adjacent”? How can someone spend a lifetime striving to get back to the Beginner’s Territory?

We’ll draw on both Takuan’s writing here and also a poem by Sen no Rikyū I absolutely love.

First, Takuan:

In this one sees the sense of the beginning being the same as the end, as when one counts from one to ten, and the first and last numbers become adjacent.

And again, using music as an example:

In other things—musical pitch, for example, when one moves from the beginning lowest pitch to the final highest pitch the lowest and the highest become adjacent.

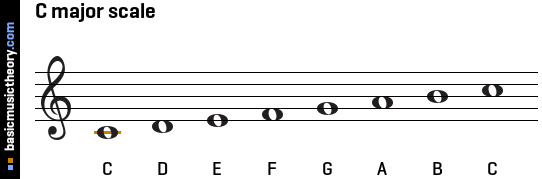

Folks not familiar with musical scales may be confused by this. Let me use a basic scale to illustrate the concept. I’ll use the C Major scale as an example for its simplicity:

(Source: Basic Music Theory)

Here we can see the beginning and the end of the scale is the C note. If we simply say the C scale begins and ends with “C”, we imply they are the same note, but they aren’t. This is because the “high C” is a full octave (i.e. level) above the “low C”.

This is how beginners and masters come to resemble one another. They are similar in appearance and yet entirely different in their position.

Now to Rikyū on the subject of practicing:

稽古とは/一より習い/十を知り/十より帰る/元のその一

keiko to wa/ichi yori narai/jū wo shiri/jū yori kaeru/moto no sono ichi

Practice involves/beginning to learn from one/and coming to know ten, then returning from ten to the original one.

– Sen no Rikyū

I love this poem because it embodies not only the spirit of learning in tea, but the spirit of learning in life.

To me, the important part of this lesson is “knowing ten” then returning to “the original one”.

In keeping with the theme of music, ask an advanced musician about how they look at music and many of them, in my experience as a musician, will say it’s about feel. To me, what this means is they’ve plumbed the depths of their craft (“knowing ten”) and now “just” play, the same way a new guitar player might “just play” out of their own ignorance and lack of awareness.

I’ve heard some musicians describe this as “forgetting everything you know”, or learning the rules and then “forgetting” them.

This is “the original one”—only they are not the same place. They are adjacent.

Mastery is “Mindless”

A bit more from Takuan before we put this subject to rest for today:

We say that the highest and lowest come to resemble each other.

…The ignorance and afflictions of the beginning, abiding place and the immovable wisdom that comes later become one. The function of the intellect disappears, and one ends in a state of No-Mind-No-Thought. If one reaches the deepest point, arms, legs, and body remember what to do, but the mind does not enter into this at all.

This is what is means to express one’s mastery over something. In simple terms, you can call this “muscle memory”, but I think that’s an oversimplification of what’s actually occurring here.

When I was in the military, we used the phrase “train like you fight”. This wasn’t simply a pedagogical method, but rather a tool for removing the thinking from the fighting when soldiers found themselves in combat situations.

In the last email, I used the example from Takuan of fighting ten men with swords and talked a bit about “proper action”. I believe muscle memory is what allows proper action to take place, because the mind is not stuck in what to do and simply takes action according to its wisdom, but that’s not all that is happening.

The body, as a tool, moves according to the mind, but the mind does not “enter” into it at all. In this way, our body and our limbs become mere extensions of the mind. Whether we’re armed or unarmed, we can take proper action in the appropriate time.

The musician does not think about the scales. The warrior does not think about the sword. The tea master doesn’t think about the whisk.

They “just” do. And that is the essence of “returning to the original one”—leaving the Beginner’s Territory, only to return to it with mindless mastery.

—

That’s it for today. I’ve got a couple more editions stacked up on the subject of mushin and various aspects of life. From there, we’re moving on to some new territory.

Now’s a good time to subscribe so you don’t miss out. If you enjoyed this post, sharing it with a friend helps me out a lot.

Take care and happy drinking.