Welcome to the Complete Guide to Matcha

Table of Contents

Welcome to The Tea Letter’s Complete Guide to Matcha! I intend to keep this post updated over time with additional links, info, and resources about matcha.

Please feel free to reach out with feedback, proposed additions, or anything else you’d like to say about the post by using the Contact form on the site.

Let’s get to it.

The History of Matcha

It may surprise you to learn tea is not native to Japan. In fact, tea was brought to Japan from China by Zen monks, who traveled to China and returned with seeds to be planted at home.

Earliest accounts of tea in Japan date back to the 8th and 9th Century, but the tea made back then was mostly very bitter leaves steamed and pressed into hard blocks for storage. That tea would then be boiled and mixed with various spices and additives (even onions of all things!) we wouldn’t recognize as tea today.

It wasn’t until the 12th Century that Eisai, another Buddhist monk, returned from China with fresh seeds and, more importantly, knowledge of the Chinese Song Dynasty’s style of growing, producing, and preparing whisked tea. Thus began the history of the matcha we know today.

What is Matcha?

Matcha (抹茶), which literally means “powdered tea”, is a green tea powder made by grinding whole leaves into a fine size perfect for whisking with hot water.

True Japanese matcha comes from Japan. This is an important distinction and I recommend paying close attention to the packaging to make sure you know your matcha’s country of origin.

Nowadays, many matcha teas passed off as authentic are actually grown in places like China or Vietnam. It’s not that there’s anything inherently wrong with these countries making matcha, but there is a large gap in quality due to experience, technology, and rigorous standards of agriculture and production that exist in Japan but not elsewhere.

Like all tea, it comes from the Camellia Sinensis plant. Tea plants destined to become matcha are grown like any other green tea plants until just before harvest time, when absolutely everything changes.

How Matcha is Grown

Matcha tea bushes are grown in full sunlight, until about 5 or 6 weeks before harvest (usually mid-April). At this point, tea farmers will begin to erect awnings over the tea bushes and cover those awnings so the tea plants are shaded.

Traditional farms will use rice straw to build their covering, though most farms favor a synthetic black material due to the costs savings in terms of labor and materials.

The reason why the tea plants are shaded is to trick the plant into thinking it’s starting to starve. As less light hits the plant, the plant responds by forcing more nutrients into the top leaves to increase efficiency of photosynthesis. The nutrients forced to to the top in this way are primarily in the form of L-Theanine, an amino acid responsible for the umami and sweet flavors in matcha.

This also prevents the bush from effectively converting L-Theanine into bitter compounds like caffeine and catechins, which can spoil the end matcha product with bitterness.

The whole shading process requires careful management and skill, as overly shading the plants may put too much stress on them, resulting in a lower yield quantity or quality. On the other hand, under-shading plants may result in a subpar product that cannot be sold as a high quality matcha.

How Matcha is Processed

It’s time to harvest! How harvesting is done is the subject of another article, but in general terms the more manual the picking process (i.e. by hand versus by machine), the higher quality the harvest.

One of the most common forms of harvesting is done in three-man teams. These teams use a machine that effectively trims all the top leaves and blows them into a large cloth sack for gathering. Two people on the team manage the machine while the third manages the collection bag.

After the harvest, the fresh leaves are turned into something called tencha, which are flat, dried leaves that almost resemble fish scales.

How Tencha is Made

It all starts with fresh leaves coming in from the fields. They are immediately steamed to stop the oxidation/fermentation of the leaves in a process called “killgreen”. This step is important because it locks in the freshness of the leaves by stopping the enzymes that promote oxidizing. Other teas, such as oolong or black teas, encourage oxidation to reach a certain level before stopping.

Once the leaves are steamed, they go through a high-temperature drying process in which they are blown up in the air inside long vertical nets. They then fall on a conveyor belt to go through another high-temperature heating process. At this point, the semi-finished tea is known as aracha. Many farmers will move the aracha into cold storage at this point, only taking it out to complete the matcha process on an as-needed basis in order to ensure maximum freshness.

If the leaves are intended to be made into matcha right then, the process continues. The stems and veins are mechanically removed (some teas that are not matcha do not go through this step), and the leaves are dried and sorted for final packaging as tencha.

This video from Obubu Tea Farm does a good job of showing the process from start to finish (~4 minutes):

Matcha Grinding

How matcha is ground makes a big difference in quality.

Lesser quality matchas will have a noticeably coarse and grainy texture. This is due entirely to how finely the leaves are ground during the processing phase. Top-tier, premium quality matcha is ground to a diameter of 5 microns. At this size, the powder particles are most likely to blend smoothly into water when whisked, ensuring a smooth and creamy texture.

Improper whisking can still result in an unpleasant drinking experience, but if the matcha is not high quality then no amount of technique will make up for its physical properties.

Stone-Ground Matcha vs. Steel-Ground Matcha

Making matcha in the traditional way requires the use of stone mills. Modern farmers who adhere to this technique might use commercial stone mill setups such as the one seen in this video:

The heavy pieces of granite are carved in such a way to ensure the leaves are properly ground in order for the powder to meet its specifications. This is a slow and costly process, but it’s an absolute requirement to guarantee the highest possible quality matcha product.

Another component of the milling process is the speed at which the mills rotate. Heat, along with light and oxygen, is the great destroyer of freshness in tea–especially anything fresh like green tea and matcha. Friction must be managed to keep heat levels low to avoid destroying the desirable volatile chemicals and nutrients that make up the stuff we love and prize so much in our fresh teas.

Read: Stonemill Matcha, San Francisco’s Best Matcha Cafe

Heat is the Tea-Killer

Unfortunately, the allure of profits and demands of efficiency have led many producers to cut corners in the manufacturing process. Steel mills are cheaper, but create a coarser powder that is unable to reach the quality of stone-ground matcha due to cutting rather than grinding the leaves.

There is also the problem of friction I just mentioned above, which degrades the flavor and quality of the tea. Steel mills will spin faster, damaging the tender leaves and reducing overall quality.

This type of approach is commonly found among growers outside of Japan, such as China, but also can be found in Japan. The overall result is a much lower quality tea. If you’re lucky, the producer is honest about their sources and methods and prices the product accordingly. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. This problem with transparency in tea is what leads many customers to have problems purchasing teas like matcha without seeing and tasting it first.

I’ll mention some of the matcha companies and brands I shop with further down in the post.

Matcha Grades: Ceremonial Grade, Latte Grade, Culinary Grade

With such a large variety of matcha types available, let’s talk a bit about grading and how to identify high-quality matcha.

Matcha Grades and What They Mean

Here’s a fun fact: Japan does not grade matcha in the same way you typically see in the States, for example. There is no “culinary” or “latte” grade. There’s not even an official designation for “ceremonial” grade. It’s all priced according to its quality, which is a product of the growing and manufacturing process we just discussed.

That said, let’s talk a bit about the way most consumers outside Japan will interact with labels to understand the type and quality of matcha. Here are the most common quality labels:

- Ceremonial Grade

- Latte Grade

- Culinary Grade

Let’s take a look at each one and talk about what kind of quality they represent.

Ceremonial Grade Matcha

Truly premium matcha deserving of the label of Ceremonial Grade is made from the best leaves of the first harvest. This first harvest, known as ichibancha, is prized for its strong umami, subtlety, complexity, and depth of flavor.

The title of Ceremonial Grade is supposed to be reserved for teas worthy of being used in formal tea ceremony. That is, making matcha in either the usucha (pronounced oo-soo-chah, lit. “thin tea”) style or the koicha (pronounced ko-ee-chah, lit. “thick tea”) style with no flavorings or additives.

(Note: Usucha is likely the style of matcha most people are accustomed to seeing–picture a bowl of matcha with the lovely green froth on top–but koicha is usually the climax of a formal tea ceremony.)

The reason why this distinction matters is because only the absolute finest teas can be prepared as koicha. Due to the strength and concentration of koicha, it must be balanced in such a way to avoid bitterness while providing a strong umami flavor.

The bad news about Ceremonial Grade is it’s really not a useful label at all. I’ve found matcha in Whole Foods claiming to be “Ceremonial Grade” that I wouldn’t dare serve whisked for a guest. In this way, the label is nothing more than marketing designed to catch the uninformed consumer, much like other food labels such as “organic” or “vegan” and “gluten free” can be meaningful but also appropriated for marketing purposes.

This is why it’s so important to arm yourself with knowledge and only shop with trusted suppliers of quality product.

Latte Grade Matcha

As the name implies, the Latte Grade matcha is intended for use in mixed drinks like the latte. There’s usually a dairy milk or mylk alternative (oat, soy, or almond milk are most common) involved, but really this label is used to dress up matcha of lesser quality.

It’s not all bad. If you’re going to heap additives into your matcha or use it blended for a smoothie then you don’t need the top-drawer stuff.

That said, there’s no reason why you have to use Latte Grade for your lattes or milk tea drinks.

I commonly use Ceremonial Grade matchas in milk tea drinks and lattes I make for myself or my wife at home. Then again, I’m not someone who’s piling additives into their drink, either. Water, matcha, milk, and maybe ice are my main ingredients. I want to taste the matcha so it has to be good.

Once again, if you’re making a smoothie or a drink where matcha is only one component of many, then there’s no point in using something that is higher on the quality scale. This is an appropriate time to use Latte Grade rather than Ceremonial Grade.

Culinary Grade

Like the name itself implies, this is matcha used only for incorporation in cooking and baking. It’s ground roughly and usually made of second or, more likely, third harvest material nobody wants to drink by itself. This is usually the type of matcha used to make matcha cheese cake, ice cream, croissants/pastries, and so on.

Primary uses for Culinary Grade matcha includes adding a smooth or creamy texture to cakes or ice cream or creating a base of bitterness and astringency for extra depth and complexity of flavor.

Many grocery store matchas claiming to be Ceremonial Grade are actually somewhere around this level. Since you’re expected to mix it with sweeteners, flavorings, and other additives, they can get away with calling it “Ceremonial” to add a buck or two to the price.

Beverage companies frequently use leaves of this grade for their Ready To Drink bottled products.

If you try and drink this by itself you’re gonna have a bad time. Expect it to be grainy and powerfully bitter, with very little to offer in the way of redeeming sweetness or character.

Save it for the cheesecake or a blended smoothie.

Matcha Quality: How to Test Matcha Quality

I’ll start with the bad news: it’s basically impossible to truly know the quality of any tea at all without tasting it yourself. That said, there are a few things you can do to give yourself the best chance of buying quality matcha up front.

Sample If You Can

If you’re buying from a local store, ask to sample on the premises. There is no better way to discern whether you’ll like a tie or not other than tasting it yourself. If you don’t get the chance to taste in person, consider a sample from an online vendor (assuming one is available).

The good news is, more and more vendors are starting to make matcha samples available online. Barring that, some vendors will highlight entry-level matchas at a budget-friendly price to get your started.

If you want to know what look for when tasting a matcha, find more info on that right below this section.

Visual Appearance

Vibrant green powder is the most obvious mark of fresh matcha high in polyphenols and amino acids. Generally speaking, the older the matcha, or the lower the quality, the less color in the powder.

Since it can be difficult to tell similar matchas apart as piles of powder, a simple technique to get a better sense of color is to do the “smear test”:

Place a small amount of matcha on a white piece of paper, take your finger and smear the matcha down the page in a straight line. Do this for every matcha one after the other to find noticeable differences in color quality.

Since even the highest quality teas will still lose their luster over time, in addition to checking for general quality this method may help you identify whether a vendor properly stores their tea before shipping to their customers.

Packaged Date vs. Harvest Date: Is Fresher Always Better?

There’s a noticeable difference in taste depending on what the producer decides when to finish making stored tea into matcha, but this is also an important indicator of freshness. If the shop you’re buying from doesn’t include this on the packaging, feel free to ask. If they don’t know the answer, maybe you shop elsewhere!

If you buy matcha produced and packed six months ago, you’re getting an inferior product. It’s not that matcha goes bad per se, but rather it loses what makes it desirable in the first place. Don’t pay same price for old matcha.

That said, there are some surprising facts about the value of getting matcha made with the freshest leaves versus letting a little time pass first.

A Little Age Never Hurt No One

What would you say if I told you the freshest matcha isn’t necessarily the best? Would it surprise you to hear me say tencha is often aged a few months before producers grind it into matcha? Indeed, many high-end matcha producers believe matcha benefits from a short period of aging to mellow out some of the sharp astringency found in fresh harvest green tea (commonly known as shincha, or “new tea”).

If absolute freshness is what you’re going for, then look for a shin (new/fresh) matcha, but don’t write off a matcha just because it was harvested a few months prior!

Country of Origin

What I said in the beginning of this post bears repeating: I feel strongly if you want good matcha you buy it from Japan. Other countries are working on matcha production, most notably China, but none of them have reached the level of quality that exists in Japan. Make sure to check the packaging before you buy.

Given the tea industry’s transparency issues, some companies will still hide behind such labels as “packaged in Japan”. This just emphasizes once again the importance of trusting the source.

Matcha Safety: Radiation and Heavy Metal Testing

By and large I have not heard of heavy metal and radiation contamination being an issue within premium matcha. That said, don’t hesitate to ask the vendor for testing reports and the like if you’re concerned about pollutants in your tea.

You could also simply buy JAS/USDA-certified organic matcha exclusively to more or less avoid the issue entirely.

What Does Matcha Taste Like?

This is a hard question to answer concisely because taste can be so subjective, but there are objective markers of quality you can look for in a well-prepared, quality matcha:

- Common flavor notes: Grasslike/vegetal, herbaceous, nutty, and marine (seaweed, ocean water, salty ocean breeze)

- Pleasant umami sweetness and flavor at some level (some debate about whether umami is a feeling or a flavor)

- Balanced bitterness and astringency that feels crisp and bright on the tongue (organic matcha complicates this)

- A lingering aftertaste and aroma in the throat, mouth, and nose

- Emerald tea liqour with bright green froth

- Smooth, creamy texture (if properly prepared)

Use these as guidelines for identifying the flavor and quality of matcha. I’d like to talk a little more about the details here below.

More Umami Is (Usually) Better, But Not Always

Tea leaves destined for matcha are cultivated primarily for maximum L-Theanine content. It’s why farmers shade the bushes and it’s also why they prefer non-organic to organic fertilizers (more on this below).

The most premium matchas I’ve tasted are what I lovingly call umami bombs. These matchas command your attention, forcing you to sit down and do nothing but pay attention to their depth and complexity.

That said, I’ve had some light and crisp matchas ideal for pairing with traditional Japanese sweets that were a joy to drink. Some of them are great for regular daily drinking. See my post on taste-testing three matchas from Ippodo Tokyo for more on what that experience can be like.

Organic Matcha vs. Non-Organic Matcha: Is Organic Matcha Better?

The topic of organic matcha is an interesting one. On the one hand, non-organic fertilizers (generally rapeseed oil and other things high in nitrogen) are not inherently bad for the human body, they do have an environmental impact (eg. algae blooms in rivers and streams). Despite this, non-organic teas and farms are the most common in Japan by a longshot. Why is this? L-Theanine.

Organic fertilizers have two weaknesses: they lack the potency to deliver the same level of L-Theanine farmers strive for in their matcha. They could use more, but turns out heavier use of organic fertilizer causes another problem: insect infestations. This increase in pest activity paradoxically leads to heavier use of pesticides, leaving us back where we started.

Further more, there isn’t much of a push inside Japan (still the majority consumer of Japanese tea) to go organic, meaning research and development into organic fertilizers is heavily unincentivized.

That said, there is plenty of good organic matcha on the market if you have a strong preference.

Flavor Impact: Organic Matcha vs. Non-Organic Matcha

There’s no way around it: organic matchas generally have stronger bitterness and astringency than non-organic matchas. This can make organic matchas a disappointing experience for matcha drinkers more accustomed to their sweet umami matcha treats. The increased effort in producing a fine quality organic matcha can also result in an increase in price, which makes it even harder to sell when non-organic matchas are out there undercutting prices.

If buying organic is important to you, then you should be ready for a different experience.

I’ve done a side-by-side with a handful of organic and non-organic matchas from the same farm (will post on this if I can find my lost notes, *sob*) and the difference was striking. I recall the top-grade organic matcha I had being powerful and deeply complex. It was definitely astringent and bitter, but it was backed up by some serious goodness.

Bitterness Isn’t Bad, Per Se

As an American, I feel oftentimes my fellow Americans are not comfortable with bitterness. Looking around at all the sugar-laden products many of us consume on a daily basis, it truly comes as no surprise. Outside of black coffee and beer, there’s not much bitter in our beverages.

My fellow Americans, I’m here to tell you: some bitterness in matcha is a desirable quality!

It’s the feeling of tension before the deeply satisfying swallow reveals sweetness and freshness. It’s the tinge of sadness at the parting between friends and family that reminds us how sweet the encounter was. It’s also a sign of a food high in antioxidants!

If you’re a dark chocolate lover, think about what happens when you hit 80% or even 90% dark chocolate. For some people, bitterness at that level feels strong enough to peel paint off a wall, but many chocolate enthusiasts look for that deep bitterness. Why? Because of the sweet payoff afterwards. Many great matchas are the same.

Don’t Confuse Bad Tea With Unskilled Preparation

Even the best quality tea can be made to taste poorly. Especially keep an eye out for this when reading tea reviews online. Without pictures or talking to the reviewer, the reader is often left to assume the skill level of the writer. A healthy dose of skepticism in favor of personal experience goes a long way here.

Be careful with temperature, powder to water ratio, and whisking style. Tea in general has very few inputs, so even small mistakes made in one way or another can have an outsized impact on the outcome.

Next let’s get to the good stuff: how to make a bowl of matcha!

How to Make Matcha

There are three ways to make a basic bowl of matcha: whisked, stirred, and shaken. I’ll cover each of them briefly here because I plan to write a more in-depth post later. I’ll add it to this post when it’s done.

A quick word on buying matcha tools: other than a bamboo whisk, which I think anyone paying the money required for good matcha should invest in, everything else is optional. I encourage use of a chashaku and specialty chawan, because they’re both surprisingly affordable and add a lot to the aesthetics and feeling of the experience.

Now, on to the details.

How to Whisk Matcha

I made a video on YouTube to go through the whole process of making matcha from scratch. If you don’t feel like sitting through the video, read on below for text instructions.

Matcha Tools & Utensils

To make a simple bowl of whisked matcha, here’s what you’ll need:

- Bowl or chawan

- Scoop or chashaku

- Bamboo whisk (chasen)

- Water of good quality (filtered or bottled spring water such as Crystal Geyser)

- Kettle or water-heating device

- Ceremonial Grade matcha

- Towel

- Sifter (optional)

Get yourself a bamboo whisk from a trusted source. See the recommended brand list below for my personal favorites. A starter whisk usually costs somewhere around $20-30, depending on quality. Don’t over-invest if this is your first time.

Instructions

- Heat your water. You’re aiming for 70-80C, or 160-175F.

- Higher temperatures emphasize fragrance and astringency. Lower temperatures emphasize umami.

- If you don’t have a temperature-controlled kettle, either heat the water until small “fish eye” bubbles are forming, or bring to a gentle boil and pour into another vessel (eg. glass measuring cup or ceramic bowl). Wait 10-15 seconds for water to cool and then use.

- Use the heated water to warm the matcha bowl.

- Place your bamboo whisk (chasen) into the warm water with the handle laying on the rim of the bowl. Gently lift and rotate a couple times so the whole whisk is moistened. Remove and set aside.

- Pour out the water and dry the bowl thoroughly.

- If you’re using a sifter on top of the bowl, place it on the bowl now. If you’ve pre-sifted your matcha, scoop directly into the bowl.

- Use your teaspoon or chashaku to spoon 2 grams of matcha into the sifter and use the scoop/chashaku to gently sift the matcha until completely sifted. Remove sifter and scoop and set aside.

- Add 60mL/2 ounces of hot water to the bowl.

- If you’re not confident with this bit, you can measure out the water quantity beforehand and pour it into your bowl. Make a mental note where the water line is on your bowl of choice.

- Take the whisk and hold it in between your index finger, middle finger, and thumb. From the wrist, whisk vigorously but not forcefully in a “M” or “N” shape. Start from the bottom (but don’t press your whisk onto the bottom of the bowl to avoid damaging the tines) and whisk until a good froth emerges, usually 10-15 seconds. Then, lift the whisk up so you’re just whisking the foam. Gentle whisk away the bubbles until you reach an almost meringue-like consistency with no large bubbles.

- Set the whisk aside and enjoy your matcha!

- Make sure you clean your bowl and tools off afterwards. If using a chashaku, do not rinse it with water. Instead, wipe it clean with a tissue or towel.

How to Make Matcha Without a Whisk

If you’re looking for a matcha whisk alternative, there are other ways to make a good bowl of matcha. While the whisk is objectively the best, here are a few options for making matcha without a whisk:

- Buy an electric frother like this one.

- Shake vigorously in a mason jar or tumbler.

- Simply stir with a spoon (make sure to sift the matcha before hand to ensure proper blending).

In all cases, you can follow the exact same instructions as above for most steps, simply replacing the portions that meet your needs accordingly.

Matcha Storage: How to Properly Store Matcha to Protect Flavor and Freshness

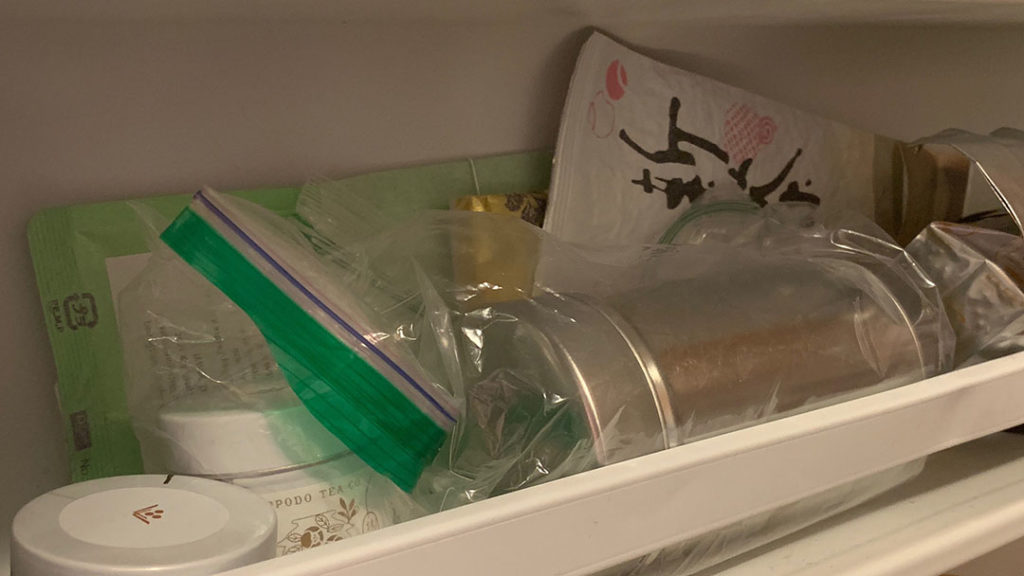

Matcha storage is a simple process but an important one. Out of all green teas, matcha powder is most susceptible to oxygen and moisture. Here are the steps I take to store matcha:

- Keep unopened containers of matcha in the freezer or the fridge.

- Once a matcha tin is opened, either move it to a better storage container (eg. a tin with a silicon gasket) or keep it in the original packaging. Then, put it in a ziploc bag for extra protection.

- If you’re planning on using up the matcha in 1-3 months, you can leave it out of the fridge somewhere away from light and heat. If you’re drinking less frequently, put it back in the fridge and only take it out 4-8 hours before you intend to drink it again.

- It’s very important to let matcha just out of the fridge come to room temperature. This will avoid any condensation and moisture forming inside the container after you’ve opened it.

Those are the basics! Here are a few extra tidbits I’ve learned from personal experience:

- Some tins come with pull tabs and some come with the matcha bagged inside. If the matcha is bagged then I leave the matcha in the bag, in the tin. The more protection I can afford my precious powder the better.

- If you want to pre-sift your matcha, you can, but this will make storage even more important as the sifting process exposes all of the tea to light and oxygen. Try sifting only what you think you’ll consume in a week.

- Matcha doesn’t really go bad, it just loses its luster. If you’ve got some older matcha that’s not as enjoyable to drink by itself anymore, try using it in blended drinks or cooking instead!

Matcha Health Benefits: Separating Fact from Fiction

I’ve saved this section for last for one simple reason: discussing the health benefits of matcha and tea is a minefield.

While some folks seem to be perfectly happy to make objective assertions of fact when it comes to this subject, I prefer to be err on the side of caution. I’m going to write a more in-depth piece on this, so for now I’ll talk a bit about what we think we know about matcha’s health benefits.

Polyphenols, Flavonoids, and Catechins in Matcha

For starters, let’s talk about polyphenols and catechins. Here are a few things to know:

- Polyphenols are a category of various compounds found in plant products and are particularly abundant in tea.

- Under polyphenols are a category of compounds called flavonoids, which are the actual compounds most people get excited about when talking about tea and plant superfoods.

- Catechins are a type of flavonoid, the most-discussed of which is epigallocatechin-3-gallate, commonly known as EGCG-3. As much as 30% of the dry weight of tea leaves is believed to be made up by catechins. (1)

- Numerous studies using animals show a noteworthy impact of catechins, EGCG-3 in particular, on cancer, cardiovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other aging-related disorders.

- Of all teas, matcha is generally highest in EGCG-3, with one study suggesting up to 60% of matcha’s catechins are comprised of EGCG-3.

L-Theanine: Matcha’s Super Power

While most people are aware of the above benefits of tea or green tea in general, I think what those same people are missing out in is the real power of matcha: L-Theanine.

L-Theanine is an amino acid found exclusively in tea and the occasional mushroom. What’s so great about L-Theanine? It’s the “zen” part of tea everyone enjoys so much (myself included).

Here’s more about it:

- L-Theanine has an “antagonistic” effect on caffeine, meaning it helps keep you feeling calm and focused instead of wired and jittery.

- It also promotes alpha brain wave production, which is the type of low-frequency brainwave that makes you feel chill, relaxed, and, well, zen.

- Unlike other sources of caffeine like coffee and yerba mate, which have sharp peaks and troughs of energy and crashes, L-Theanine slows the release of caffeine into the bloodstream. This means you have a gentler curve of energy without the crash.

The TL;DR of L-Theanine is this: it’s what makes tea so much better than coffee. Yeah, I said it. As for matcha, it has the highest amounts of L-Theanine out of all teas. This is due to both how it’s grown (remember, L-Theanine creates the sweetness and umami of matcha) and also the fact you’re consuming the entire leaf.

There Are Good Reasons to be Skeptical

Here are the reasons you should be skeptical of anyone making objective claims about matcha’s health benefits:

- Many studies use amounts of compounds (EGCG, L-Theanine, etc.) that are not realistic or achievable in the course of regular matcha consumption.

- Animal studies cannot be reliably transferred to the human body as a 1:1 or “apples to apples” comparison.

- It’s impossible to make broad statements about quantities of various compounds (caffeine, catechins, etc.) in matcha as a whole. The impact of everything from soil to weather to processing to storage changes the chemical composition of tea.

Generally speaking, don’t take anything at face value before you look into it a bit deeper yourself. Trust me, I know it can be intimidating at first. I have no medical or academic background and have had to learn how to read studies. Start with the links in this post and remember: Google is your friend.

Matcha Sellers & Recommended Brands

We’ve made it through basically everything I wanted to cover in this post at this point, so let’s wrap things up with a list of my favorite matcha vendors (so far):

Ippodo

A Japanese classic. Ippodo has been around for 300 years and could be considered as the standard of Japanese matcha. They have a standardized selection and also a number of seasonal exclusives, though many are only available at their retail locations. Their products are very affordable, but shipping is $20, which is a bummer.

Check out my post here on the blog for more about my experience with Ippodo: Three-Way Ippodo Matcha Tasting

Kettl

A relative newcomer to the scene, Kettl is a Brooklyn-based purveyor of premium matcha and Japanese teas. I simply don’t know of anyone in the United States offering a more exciting and premium selection of products than them.

US-based drinkers will enjoy their speedy and affordable shipping costs.

Yunomi

Disclaimer: I’ve done some consulting work with Yunomi in 2019.

That said, nobody can compete with the sheer variety Yunomi has to offer. Based in Japan, they work with over 150 small-scale and artisanal producers of Japanese tea. If you’re looking to access the depth and breadth of Japanese matcha, or Japanese tea in general, look no further.

Honorable Mentions

Here are a few companies I’ve had limited experience with or know of based on reputation:

I’d love to add some more sources to this list, especially for any readers not based in NA, so please hit me up with your recommendations!

Conclusion

You made it through! Congrats! Have a bowl of matcha and chill.

Believe it or not, I still have more info I want to put in this post. I’ll be writing some extra stand-alone posts that explore some of the topics here more deeply. I’ll also add and update some info in this article over time.

If you still have any other questions, feedback on stuff I missed or messed up, or recommendations for additions, don’t hesitate to contact me on the blog or on Instagram.

Thanks for reading! If you’re not subscribed to my email list you can Click Here to do so. I’ll email you maximum once a week with new stuff from the blog.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1614995 (Graham, 1992)

4 comments

This is a really throughout guide, thank you Mike.

So glad you find it helpful! Any lingering questions left unanswered or new stuff you thought of after reading?

Another matcha seller that’s very good is Setsugekka in New York, I cant say anything for their more expensive offerings, but I can say that their yame no hana is incredibly rich for its price range, and I personally prefer it to Ippodos offering in that range.

I had the pleasure of visiting Setsugekka back in March, and I agree they are wonderful. The fact they grind on site coupled with the masterful preparation of the tea master makes it a one-of-a-kind treasure in the United States!