It’s November, and autumn has finally breathed its last breath. In the tea room, the four-and-a-half tatami mats have been rearranged to make space for the ro–a sunken hearth in the center of the room, with a squat iron kettle nestled within. Resting atop its stand above a pile of charcoal, the kettle hisses and whispers comfortably like the sound of the winds rustling the branches and needles of the matsu, the Japanese pine tree, warming the tea room.

Although the winter rains have yet to fall here in San Francisco, it’s officially winter in the world of tea.

For the tea person, the start of winter in November acts as a counterpoint to the spring season that starts in April/May. It’s like a “new year” before the New Year at the end of December. There is typically a special tea gathering held to celebrate the opening of the tea jars (kuchikiri), and the food selection for the kaiseki portion of the gathering contains many of the same foods that show up for the New Year’s tea gathering (hatsugama).

In short, winter is a momentous occasion in the world of tea.

Settling In To Winter

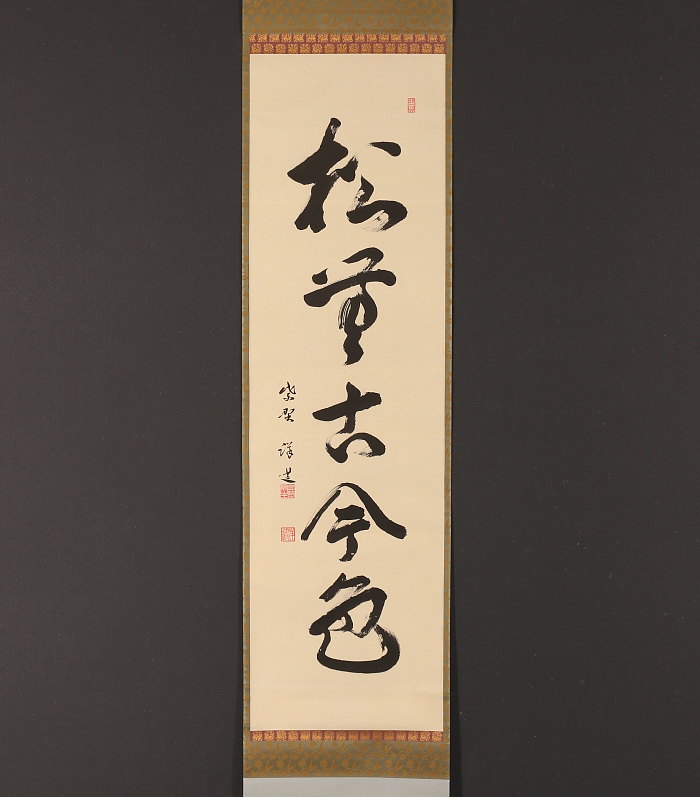

This is my first entry into the winter season as a student of chanoyu, and the changes are wonderful to see. At tea class on the weekend, my teacher hung a scroll in the tokonoma (an alcove for the display of art and flowers) to remind us of both the passage of time and the illusion of time:

「松無古今色」

matsu ni kokon iro nashi

Inscription on a hanging scroll

the pine tree has no old or new color

The Japanese pine tree is a key figure in the lore of chanoyu. As I mentioned above, the sound of the wind through its needles is said to be the sound of the iron kettle softly boiling. Sen no Rikyu himself said the nature of chanoyu is “the sound of windblown pines in a painting”.

I’ll get into what I think he means by “in a painting” in another post, but for now we can focus on the hanging scroll.

We discussed the meaning of poetic phrase, noting the symbolic meaning of “strength” coming from the evergreen nature of the pine. We also used it to discuss the nature of time and what is “real”.

The whole class practiced usucha hirademae (“basic preparation of thin tea”). The hirademae are the basic preparations one learns right after bonryakunotemae (“tray style preparation”). As I’m still working to master the hirademae, the switch to the ro from the furo took some getting used to.

The position of the utensils, the hand movement for the hishaku (bamboo water scoop), and the position of the body relative to everything else are all different for the ro-style preparation. Even entry into the tea room itself changes–the door leading from the water room to the tea room is closed, rather than left open.

Not Yet A Winter Wonderland

One thing I’m missing so far as we move into winter is the general feeling of winter itself. For the Bay Area, that means gray skies and incessant rains–the perfect excuse to bundle up inside with a bowl of warm tea. More than that, with the recent wildfires in wine country and down in southern California, we’re all hoping for the quenching release of the winter rain.

Apparently winter rains feature prominently in traditional Japanese poetry (called waka) for the month of November. As I browsed The Way Of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master’s Alamanac, I found a beautiful piece on the subject:

「長き夜のねざめの窓に訪づる、時雨は老の友にぞありける」

Inscription written on a tea container

nagaki yo no / ne-zame no mado ni / otzururu / shigure wa oi no / tomo nizo arikeru

waking during a long night, I find winter rain, a real friend for an old man, tapping at the window

I love the feeling of this poem because it reminds me the times when I also wake up to the sound of rain drops blowing against my windows. In general I love rain, and it comes so infrequently where I live that I long for the sound of it splashing on trees and grass, slapping on paved streets, and tapping on glass windows.

Embracing The Never-Changing Nature Of Time

In the Christian Bible, the book of Ecclesiastes starts out with a strong declaration: “‘Meaningless! Meaningless!’ says the Teacher.” (Ecclesiastes 1:2, NIV).

A few short verses later the “Teacher” follows up with: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” (Ecclesiates 1:9, NIV)

To me, this is saying the same thing as “the pine tree has no old or new color”. There is nothing new under the sun, so what’s real is what’s now, and what’s now is the cold breath of winter.

I will meditate on this as I listen to the sound of crunching leaves under my feet and watch the skies for winter rain.